Late (and very early) Orson Welles season

Chimes at Midnight

aka FalstaffDir: Orson Welles, 1965, Spain/Switzerland/France, Language: English, 116 mins, Cert: PG

-

Sun 27 October 2024 // 17:00

Tickets: £5 (full)

In October we’re screening three late Orson Welles films - F for Fake, The Immortal Story and Chimes at Midnight - and in November, the very first Welles film, the silent comedy Too Much Johnson.

“By several stretches, the best Shakespeare film that’s ever been made.”

—Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker

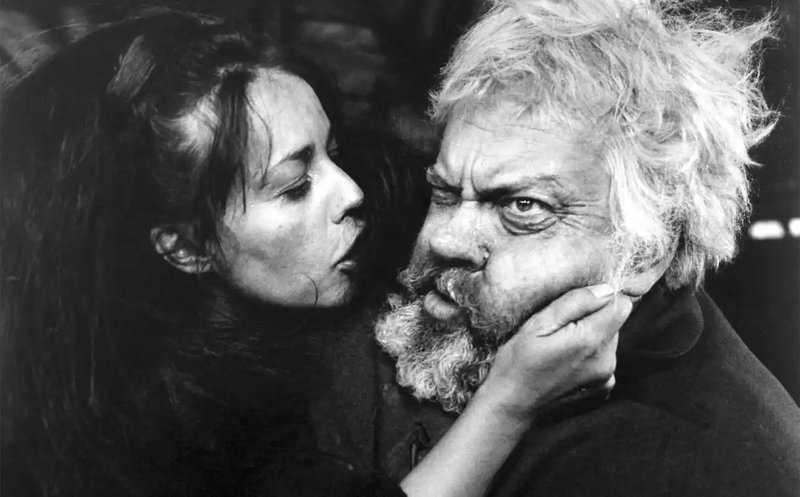

Orson Welles parlayed a lifelong fascination with Shakespeare into one of his most delightful and moving works - and Welles’ personal favourite of all his films.

Chimes at Midnight (also released under the title Falstaff) focuses on the character that Welles was born to play - Sir John Falstaff, the outsized, tragicomic symbol of “Merrie old England” (in fact, Welles had been playing the part since his twenties - in 1939, in a typical Wellesian act of gloriously misguided ambition, he attempted and failed to adapt nine Shakespeare plays into a single production called Five Kings, with himself as Falstaff). The film tells the story of Falstaff’s relationship with Prince Hal, the future Henry V, who is misspending his youth by whoring and drinking in the taverns of Eastcheap - and is fated to drift away from his surrogate father Falstaff.

Like all of Welles’ later films, Chimes at Midnight was made on a tiny budget. This freed Welles to indulge his taste for surreal, noirish cinematography - pleasantly jarring in a medieval setting - but doesn’t limit the ambition or scope of the film. In particular, it’s amazing to consider that the epic, visceral battle scenes were made in an independent production - or perhaps it was the very lack of resources that forced Welles to find a brilliantly creative approach to plunging viewers into the midst of a muddy, bloody 15th century battle.

“Now Chimes at Midnight can be watched in something near to the form that it was intended to be seen in, and it appears as one of the very pinnacles of Welles’s art, matching a forceful, visual dynamism to a melting, mellifluous reading of Shakespeare’s text. ”

—Nick Pinkerton, Artforum

“Orson Welles’ Falstaff came and went so fast there was hardly time to tell people about it, but it should be back (it should be around forever) and it should be seen. It’s blighted by economics and it will never reach the audience Welles might have and should have reached…He has directed a sequence—the battle of Shrewsbury—which is totally unlike anything he has ever done, indeed unlike any battle ever done on the screen before. It ranks with the best of Griffith, John Ford, Eisenstein, Kurosawa—that is, with the best ever done.”

—Pauline Kael, The New Republic